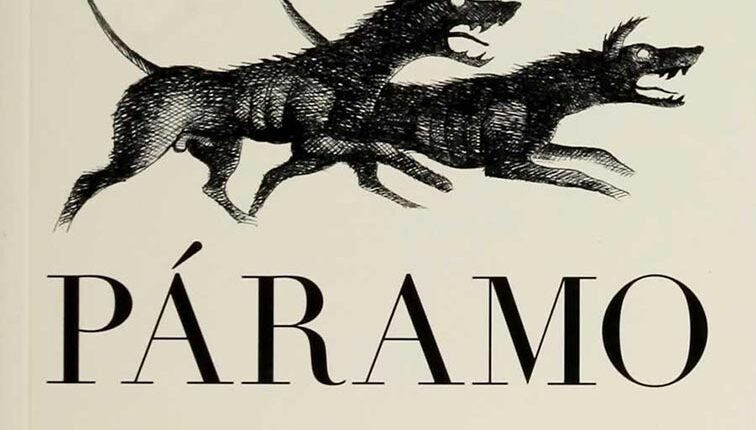

When Pedro Páramo was published in Mexico in 1955, it arrived almost without ceremony. Its author, Juan Rulfo, was not part of a powerful literary circle, nor did he have a large body of work behind him. The novel itself was short, fragmentary, and strange—hardly the kind of book that publishers or critics expected to define a literary era. Yet over time, Pedro Páramo would become one of the most influential novels ever written in Spanish, laying crucial groundwork for Latin American literary modernism and the later Boom movement. Its importance lies not in commercial success or initial acclaim, but in how radically it reimagined narrative voice, time, and the boundary between life and death.

At its surface, Pedro Páramo tells a simple story. Juan Preciado travels to the rural town of Comala to fulfill a promise to his dying mother: to find his father, Pedro Páramo. What Juan encounters instead is a ghost town, populated by murmuring voices, memories, and the lingering presence of Pedro Páramo himself—a violent landowner whose power shaped the town’s rise and decay. As the novel unfolds, it becomes clear that Comala is not merely abandoned; it is inhabited almost entirely by the dead.

This premise alone was unusual, but Rulfo’s true innovation lay in how the story is told. Pedro Páramo abandons linear narrative almost entirely. Voices shift without warning. Characters speak from beyond the grave. Time collapses, loops, and fractures. Readers are never fully grounded in a stable perspective, and the novel offers few explanations. This disorientation is not a flaw but the point: Comala exists in a kind of suspended afterlife, and the narrative itself mimics the logic of memory, guilt, and haunting.

At the time of its publication, Mexican literature was still heavily influenced by realist and revolutionary traditions. Novels often emphasized clear moral frameworks, social struggles, and chronological storytelling. Rulfo broke decisively from this mode. While Pedro Páramo is deeply rooted in rural Mexico—its landscapes, its history of land exploitation, its religious imagery—it refuses to present that reality in straightforward terms. Instead, Rulfo suggests that history is something that lingers, whispers, and corrodes, rather than something that can be neatly recorded.

Pedro Páramo himself is one of the novel’s most enduring contributions to literature. He is neither a traditional villain nor a heroic antihero. As a cacique (local strongman), he controls land, people, and destinies, driven by obsession, cruelty, and a warped sense of love. Yet he is not portrayed through a single lens. Different voices remember him differently: as tyrant, seducer, abandoned lover, grieving husband. The result is a character constructed not by authorial judgment but by collective memory. This fragmented portrait would become a hallmark of later Latin American fiction.

Perhaps the most significant legacy of Pedro Páramo is its influence on magical realism, though Rulfo himself never used the term. Unlike later works where magical elements coexist comfortably with the everyday, Rulfo’s supernatural is unsettling and mournful. The dead do not return to offer wisdom or wonder; they return because they cannot rest. Their voices are weighed down by regret, unfulfilled desire, and unresolved violence. In this sense, Pedro Páramo is less about magic than about haunting—about how personal and national histories refuse to disappear.

This approach deeply influenced writers such as Gabriel García Márquez, who famously said that after reading Pedro Páramo, he realized what literature could do. The echoes are clear in One Hundred Years of Solitude: the ghostly presences, the cyclical time, the idea of a town as a living archive of memory. Yet Rulfo’s style is more austere, more restrained. Where García Márquez expands into baroque abundance, Rulfo pares language down to its barest bones. Every sentence feels measured, almost carved out of silence.

Another reason Pedro Páramo became so important is its exploration of power and decay in post-revolutionary Mexico. Pedro Páramo’s control over Comala reflects a broader historical reality: the persistence of feudal power structures despite political change. The Mexican Revolution promised land reform and justice, but in Rulfo’s novel, those promises rot. Comala’s emptiness becomes a metaphor for a country haunted by broken ideals. Without ever becoming overtly political, the novel delivers a devastating critique of authority and abandonment.

It is also remarkable that Juan Rulfo never published another novel. Aside from a short story collection, El Llano en llamas, his literary output was minimal. This scarcity has only intensified the novel’s mystique. Pedro Páramo stands as a singular achievement, proof that literary impact is not measured by volume. Its endurance comes from precision, not productivity.

Today, Pedro Páramo is taught worldwide and translated into dozens of languages. What began as a modest, difficult book has become a cornerstone of global literature. Yet it still resists easy reading. Each return to Comala reveals new voices, new silences. The novel demands patience and attentiveness, asking readers to listen closely—to the dead, to history, to the spaces between words.

In the end, Pedro Páramo is important not because it explains Latin America, but because it refuses to simplify it. It captures a world where the past is never past, where power leaves scars that outlive bodies, and where storytelling itself becomes an act of excavation. From its quiet, indie origins, Rulfo’s novel reshaped what a novel could be—and continues to whisper its influence through literature nearly seventy years later.