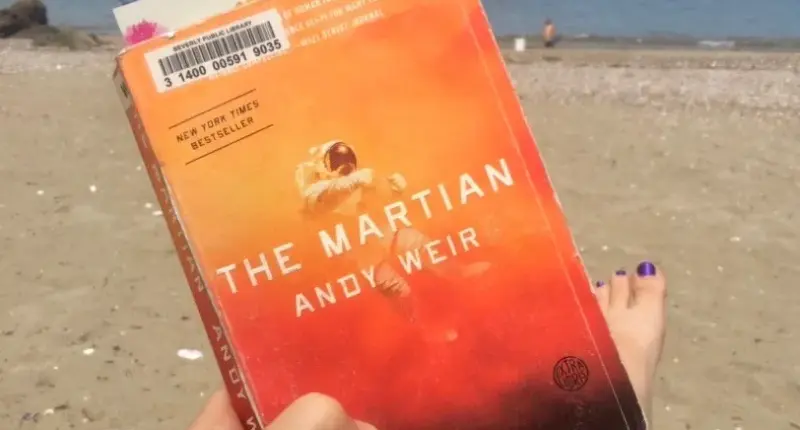

Before it became a blockbuster film starring Matt Damon, before it launched Andy Weir into literary stardom with a seven-figure book deal, “The Martian” existed as a serialized story on Weir’s blog, offered chapter by chapter to a small but devoted audience of science enthusiasts. When readers asked for a Kindle version for convenience, Weir obliged, pricing it at 99 cents—the minimum Amazon would allow. That humble beginning transformed into one of indie publishing’s greatest success stories, and more importantly, resulted in one of the most entertaining and scientifically rigorous science fiction novels of the twenty-first century.

The Setup: Alone on Mars

The premise is elegantly simple and terrifying: astronaut Mark Watney becomes stranded on Mars after his crew, believing him dead during a catastrophic dust storm, evacuates the planet without him. When Watney regains consciousness, he faces a stark reality—he’s alone on a hostile planet 140 million miles from Earth with limited supplies, no communication, and no immediate prospect of rescue. The next Mars mission won’t arrive for four years. As Watney himself succinctly puts it in the novel’s iconic opening line: “I’m pretty much fucked.”

What could have been a grim survival tale or a philosophical meditation on isolation instead becomes something unexpected: a celebration of human ingenuity, humor in the face of death, and the stubborn refusal to give up even when the odds seem insurmountable. Weir’s background as a computer programmer and lifelong space enthusiast shines through every page, grounding the narrative in meticulous scientific detail while never sacrificing the propulsive energy that makes the book nearly impossible to put down.

The Science: Hard SF Done Right

“The Martian” represents hard science fiction at its finest—a subgenre that prioritizes scientific accuracy and technical plausibility over fantastical elements. Weir conducted extensive research to ensure that Watney’s survival strategies, while creative and sometimes desperate, remain within the realm of possibility given our current understanding of physics, chemistry, biology, and engineering.

The novel walks readers through Watney’s problem-solving processes with remarkable clarity. When he needs to grow food to extend his limited supplies, we learn about Martian soil composition, the challenges of creating arable earth, and the chemistry of producing water from hydrazine rocket fuel. When communication systems fail, Weir explains orbital mechanics and the physics of signal transmission. When Watney must modify rovers and habitats for extended journeys, we get detailed explanations of power consumption, thermal regulation, and structural integrity.

What makes this technical detail compelling rather than tedious is Weir’s ability to present complex concepts through Watney’s irreverent, accessible voice. The protagonist is a botanist and engineer, yes, but he’s also someone who listens to terrible disco music, makes pop culture references, and explains his survival methods with a combination of scientific precision and self-deprecating humor. He never talks down to the reader, but he also never assumes expertise, creating a perfect balance for both science enthusiasts and casual readers.

The authenticity of the science serves a deeper narrative purpose. Each of Weir’s carefully researched solutions reinforces the central theme: humans can solve seemingly impossible problems through knowledge, creativity, and determination. When Watney succeeds, it doesn’t feel like authorial intervention or convenient plot armor—it feels earned, logical, and inspiring.

The Character: Mark Watney’s Irrepressible Spirit

Mark Watney could easily have been a generic action hero or a brooding loner, but Weir crafts something far more interesting—a thoroughly likable everyman who happens to be brilliant. His log entries, which comprise much of the novel, reveal a personality that refuses to surrender to despair even as disaster after disaster compounds his already desperate situation.

Watney’s humor isn’t a defense mechanism that masks deeper trauma; it’s a genuine expression of his personality and a practical tool for maintaining sanity in isolation. When faced with the prospect of surviving on potatoes for years, he doesn’t just calculate caloric requirements—he jokes about becoming “the greatest botanist on this planet.” When he accidentally blows up his potato farm, destroying months of work, his reaction mixes legitimate frustration with gallows humor that feels authentic rather than forced.

The character’s optimism never veers into naiveté. Watney clearly understands the precariousness of his situation and the countless ways he could die. He experiences fear, frustration, and moments of despair. But he chooses, again and again, to focus on the next problem to solve rather than the insurmountable nature of his overall predicament. This philosophy, which he articulates explicitly—”You solve one problem, and you solve the next one, and then the next. And if you solve enough problems, you get to come home”—becomes the novel’s beating heart.

The Structure: Tension Through Log Entries

Weir’s decision to tell much of the story through Watney’s log entries creates an interesting structural challenge and opportunity. The format means we know from the outset that Watney survives long enough to record these experiences, theoretically reducing suspense. Yet Weir masterfully maintains tension through the accumulation of obstacles and the ever-present question of how Watney will overcome each new crisis.

The narrative intersperses Watney’s first-person logs with third-person chapters following NASA’s efforts to mount a rescue and his crewmates’ reactions to discovering he’s alive. This structural choice prevents the novel from becoming claustrophobic and allows Weir to explore themes of collective human effort, international cooperation, and the lengths people will go to save one of their own. The scenes at NASA and with the Ares 3 crew provide emotional depth and raise the stakes—Watney isn’t just surviving for himself but for everyone working desperately to bring him home.

The pacing is relentless. Just as Watney solves one problem, another emerges. A dust storm threatens his solar panels. Communication equipment fails. Life support systems malfunction. Each setback feels organic rather than contrived, a natural consequence of operating complex equipment in an environment where the slightest error proves fatal. Weir never allows readers to settle into complacency, maintaining forward momentum throughout the novel’s considerable length.

The Indie Origins: Why This Story Matters

“The Martian” succeeds brilliantly as a novel, but its origins as an indie success story add another layer of significance. Traditional publishers initially rejected Weir’s manuscript, likely considering it too technical, too niche, or too risky for mainstream audiences. The gatekeepers were wrong, spectacularly so.

The book’s trajectory from blog serial to self-published ebook to bestselling traditionally published novel to major motion picture demonstrates the potential of indie publishing to surface stories that traditional channels might miss. Weir’s direct relationship with early readers shaped the book’s development—their feedback influenced revisions, their enthusiasm generated word-of-mouth momentum, and their support validated his decision to continue writing.

Moreover, the book’s success proved that readers hunger for intelligent science fiction that respects their intelligence. “The Martian” never dumbs down its science or panders to perceived audience limitations. It trusts readers to follow technical explanations, to care about orbital mechanics and chemistry, to appreciate problem-solving as dramatic action. That trust, combined with Weir’s accessible prose style and Watney’s engaging personality, created something that appeals across demographics—from hardcore SF fans to readers who typically avoid the genre entirely.

Final Verdict: A Modern Classic

“The Martian” earns its status as a modern science fiction classic through a combination of meticulous research, propulsive storytelling, memorable characterization, and thematic resonance. It’s simultaneously a page-turning thriller, a celebration of scientific thinking, and an optimistic affirmation of human capability and cooperation.

The novel’s influence extends beyond entertainment. Educators use it to teach scientific concepts. NASA employees cite it as surprisingly accurate. It has inspired countless readers to take renewed interest in space exploration and STEM fields. In capturing the imagination of millions, Weir’s indie novel achieved something remarkable: it made science exciting, accessible, and cool.

For readers who appreciate intelligent speculative fiction grounded in real science, “The Martian” is essential reading. For anyone who has ever faced seemingly impossible odds and wondered how to keep going, Mark Watney’s story offers both inspiration and a practical philosophy: solve one problem, then solve the next. And if you solve enough problems, you might just make it home.

Andy Weir’s “The Martian” proves that great storytelling can emerge from anywhere, that traditional publishing doesn’t hold a monopoly on quality, and that sometimes the best books are the ones that almost never found their audience. It stands as both an exceptional novel and a testament to the democratizing power of indie publishing—a fitting legacy for a book about one man’s refusal to accept the limitations others might assume insurmountable.